Introduction

In addition to the potential for growth and income and low correlation to public equity markets, private real estate’s attractive overall risk-adjusted returns are further enhanced by favorable tax treatment in the U.S. Tax benefits are a major – but often not well understood – component of real estate investments. These benefits may include depreciation, tax deferral, and pass-through of income and losses. Additionally, tax benefits often compound as the investment horizon increases and can include long-term capital gains tax rates, 1031 exchanges and refinances, and step-up in basis. This article will focus on tax concepts in the context of private real estate investments, particularly for limited partners (LPs) investing with professional general partners (GPs) and the impacts on financial returns and tax obligations of investors.

Depreciation

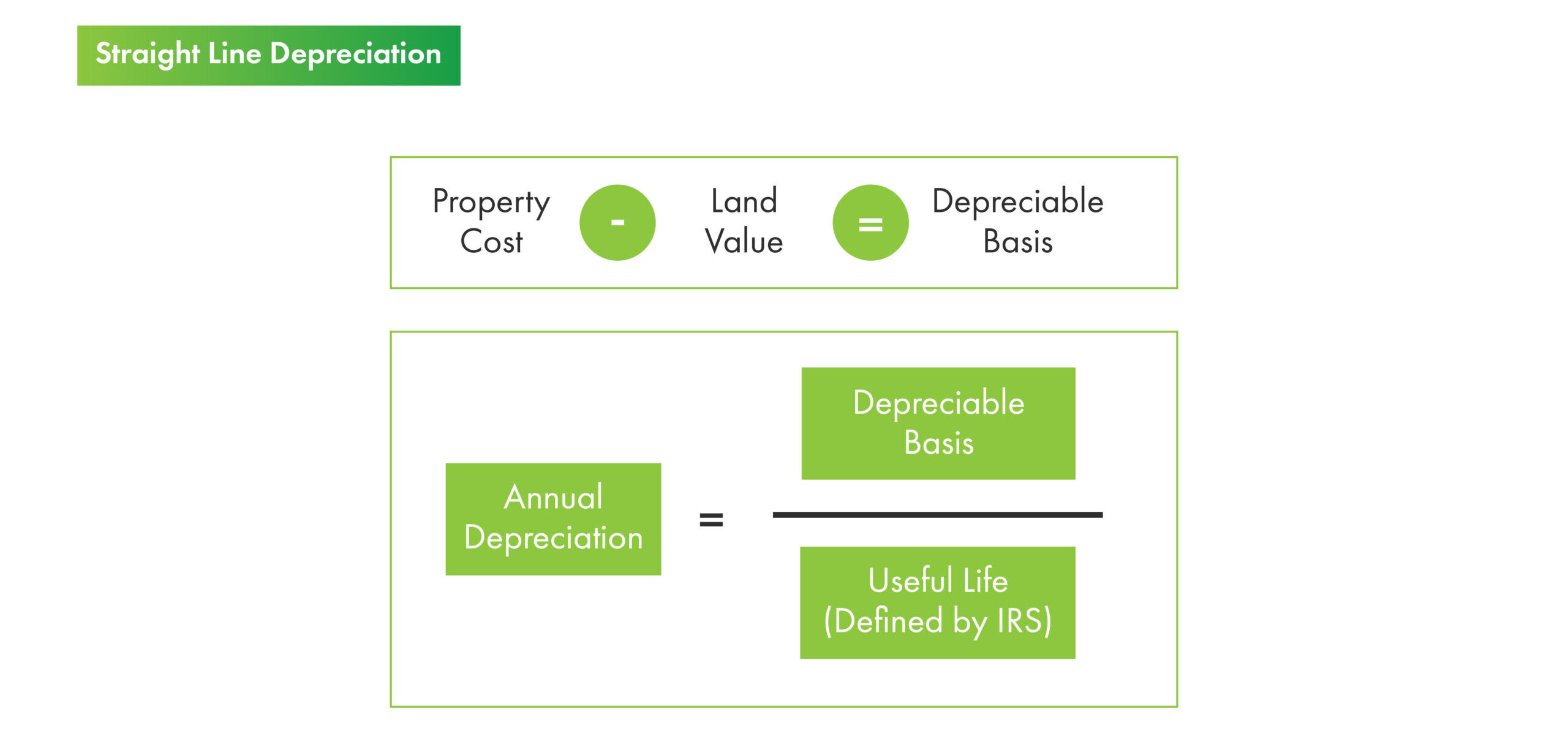

Depreciation is an accounting method that allows businesses to deduct the cost of a tangible asset, like real estate, over its useful life. It recognizes the asset’s reduction in value over time due to wear and tear, obsolescence, or aging, even if the property is increasing in market value or producing positive cash flow. The depreciable basis, used to calculate the annual deduction, is the cost of the property minus the value of the land. Since land is never “used up,” only improvements (buildings, structures, etc.) are depreciable. Depreciation is a non-cash expense, effectively reducing taxable income and enhancing after-tax returns for investors. The most common method is straight-line depreciation, where the depreciable basis is divided equally over its useful life as defined by the IRS.

Mechanics of Depreciation

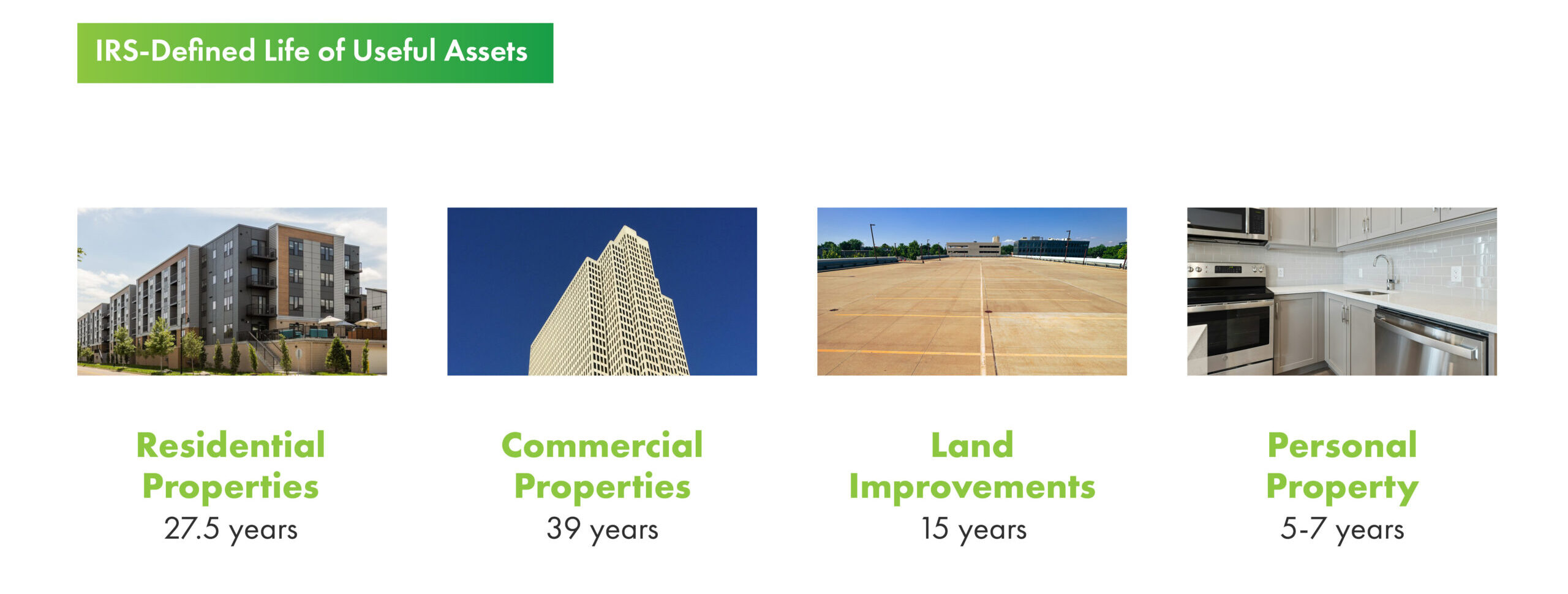

Depreciation is calculated based on the useful life of the asset as defined by the IRS and the chosen, applicable depreciation method. Residential properties (e.g., multifamily) are depreciated over 27.5 years. Commercial properties (e.g., office, industrial, retail) are depreciated over 39 years. Land improvements (e.g., parking lots, landscaping) may be depreciated over 15 years. Personal property (e.g. appliances) may be depreciated over 5-7 years.

In private real estate investments, the partnership (typically structured as an LLC) owns the real estate assets. The depreciation deductions are calculated at the partnership level, based on the depreciable basis of the assets and the applicable depreciation methods, and passed through to LPs based on their ownership percentage, or pro-rata share. The proportionate share of Net Rental Income reported on the LP’s annual Schedule K-1 includes the deduction for the depreciation (non-cash charge) taken at the partnership level. This reduces their taxable income from the investment and potentially other investment incomes.

Accelerated Depreciation

Traditional depreciation using the straight-line method spreads the deduction evenly over the asset’s useful life. However, accelerated depreciation can be used to front-load depreciation deduction in the early years of an asset’s life and potentially create tax losses that offset income.

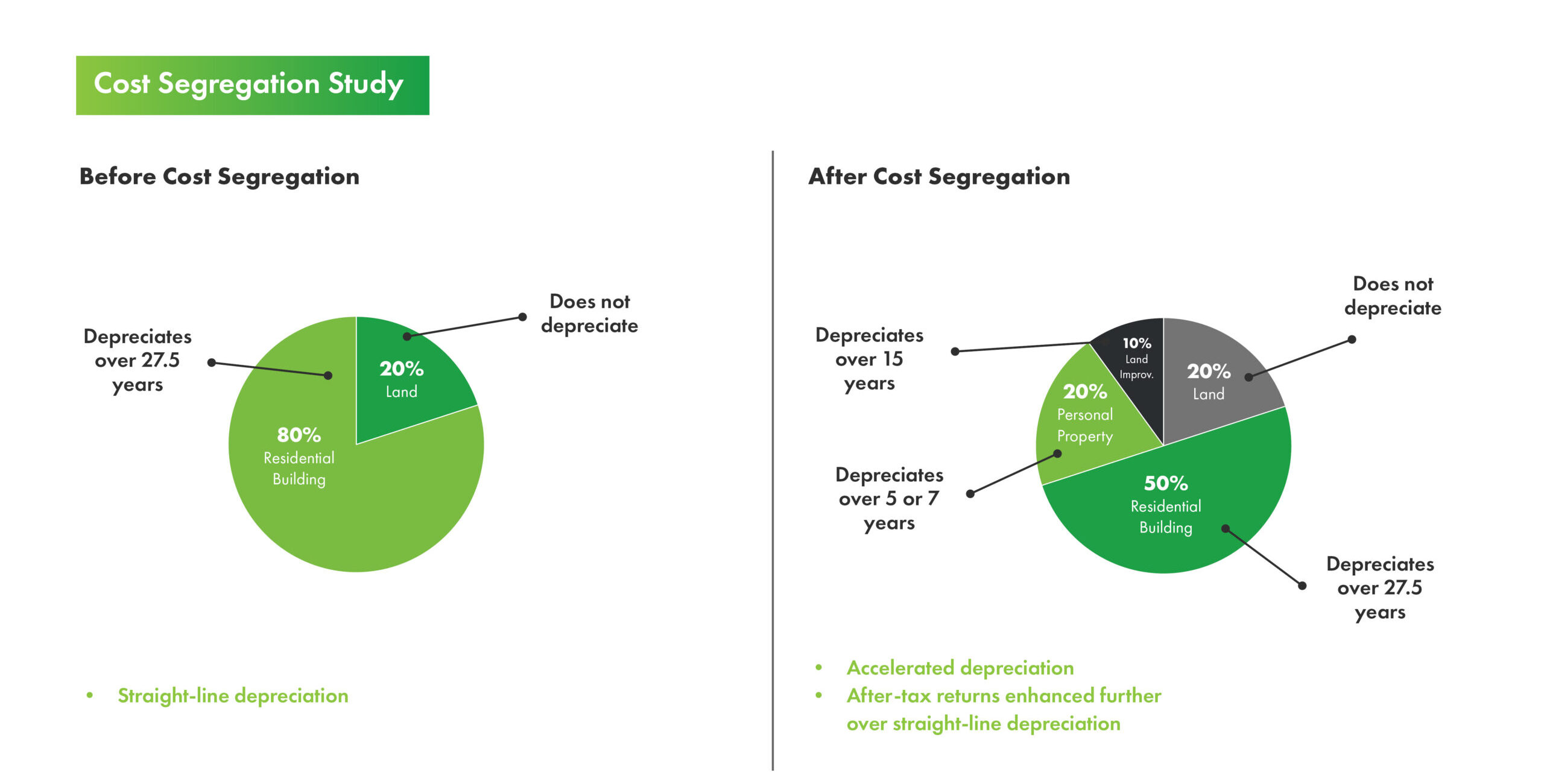

For real estate, many investors hire specialists to perform cost segregation studies to identify and reclassify certain components (e.g., fixtures, landscaping) of a building as personal property or land improvements, which have shorter deprecation periods (5, 7, or 15 years) using the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). This allows for significantly larger depreciation deductions in the initial years of ownership.

Deferred Financing Costs

Amortization of deferred financing costs aims to match the expense of obtaining financing with the period that benefits from that financing. Also known as debt issuance costs, deferred financing costs are expenses incurred when obtaining a loan. For a real estate investment, these costs can include loan origination fees, legal fees, appraisal fees, and other brokerage fees. These costs are not immediately expensed because they provide a benefit over the life of the loan. Instead, they are capitalized as an asset and expensed over the loan term through amortization. Like depreciation, amortization expenses reduce the taxable income from the partnership.

Types of Deferred Financing Costs

Loan Origination Fees: Charged by the lender to the borrower for the administrative costs of processing and underwriting the loan. They are often a percentage of the loan amount

Legal Fees: Costs incurred for attorneys to prepare and review the loan agreements, security documents (like mortgages or deeds of trust), and other legal paperwork associated with the financing.

Appraisal Fees: Costs associated with obtaining a professional appraisal of the property, which is typically required by the lender to assess its value and collateral.

Brokerage or Placement Fees: If a mortgage broker or other intermediary is used to secure the financing, they may charge a fee for their services.

Other Due Diligence Costs: This can include expenses related to reviewing property condition reports, feasibility studies, or other investigations required by the lender as part of their underwriting process.

Distributions and Taxable Income

A key benefit of depreciation is its ability to create a “tax shelter,” reducing the taxable income reported by the partnership and passed through to LPs. LPs receive cash flow from rental income or property operations as distributions from the partnership. The taxable income generated by the property is reduced by the depreciation and amortization expenses. For example, an LP might receive a $50,000 distribution but only report $10,000 in taxable income due to the deduction of interest expenses, depreciation, and other non-cash charges.

In the early years of a real estate investment, especially with accelerated depreciation, the depreciation deductions can be large enough to offset all or a large portion of the taxable income. For tax purposes, these distributions are often treated as return of capital, reducing your basis in the investment. There are some limitations to depreciation losses. Depreciation can create tax losses if the deduction exceeds income. However, passive losses can only offset passive income. Unused passive losses can be carried forward to offset future passive income or realized upon sale of the investment.

Depreciation Recapture

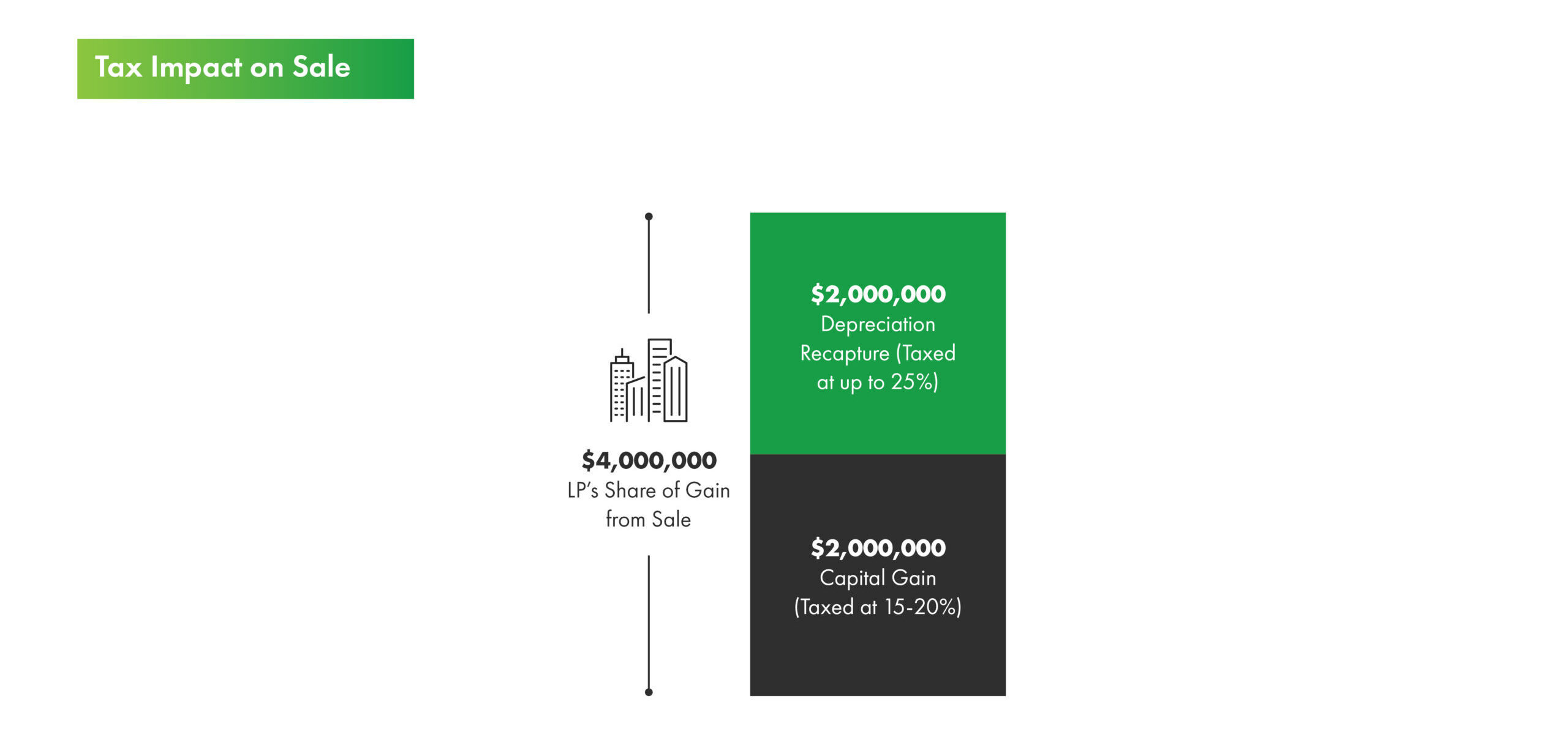

The tax benefits of depreciation are eventually “recaptured” when the property is sold. Depreciation recapture is the portion of the gain that is taxed at the 25% depreciation recapture rate. Depreciation deductions reduce the property’s adjusted basis. For example, a $10 million building depreciated by $2 million over time has an adjusted basis of $8 million. Upon sale, the portion of the gain attributable to depreciation is taxed as depreciation recapture as defined by Section 1250 Property treatment at a federal rate of up to 25%.

If the previously mentioned property is sold for $12 million, subtracting the adjusted basis results in a total gain is $4 million. $2 million, the depreciation taken, is taxed at up to 25%, and the remaining $2 million is taxed at long-term capital gains rates (15-20%). The partnership allocates the gain, including recapture, to LPs based on their pro-rata share.

1031 Like-kind Exchange

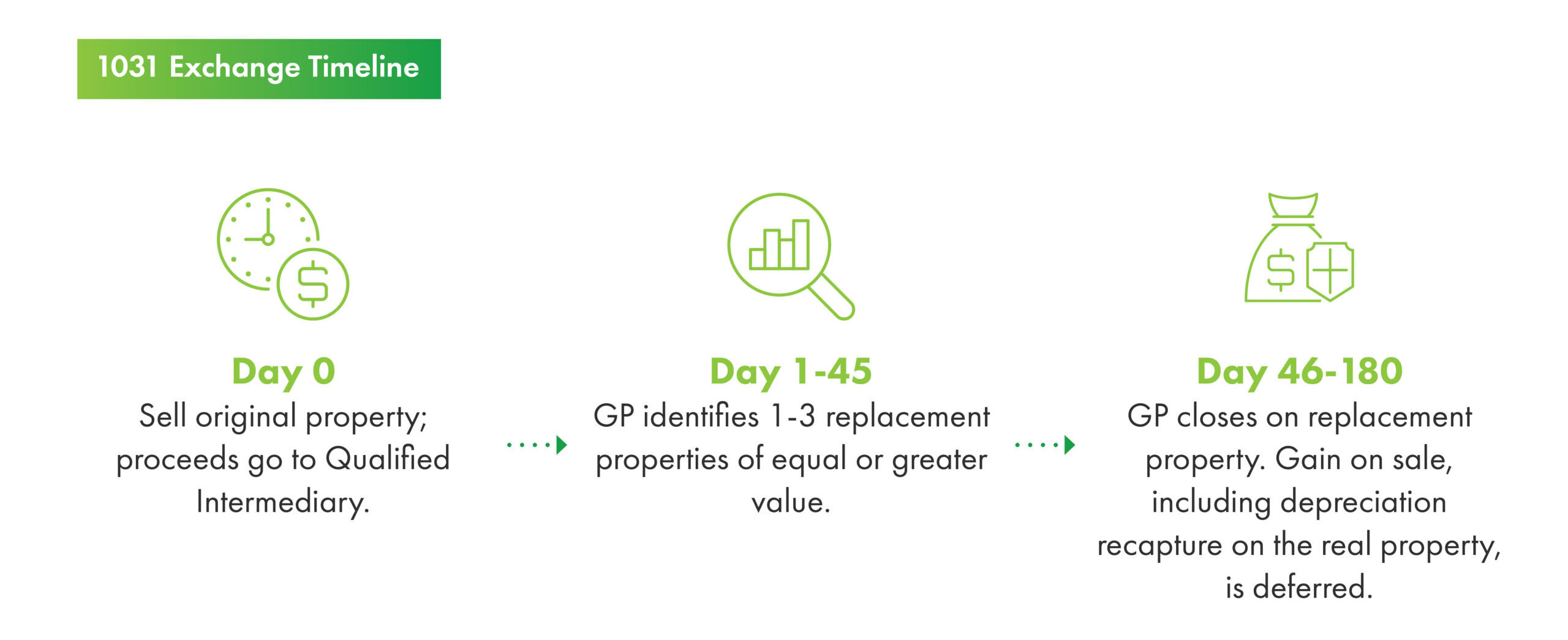

A 1031 exchange is a commonly used tool to defer capital gains taxes and depreciation recapture by reinvesting sale proceeds into a “like-kind” property. “Like-kind” in real estate is broadly defined, generally meaning any real property held for business or investment purposes.

Proceeds from the sale of a property are held by a Qualified Intermediary (QI) until they are reinvested in another real estate property (or properties) of equal or greater value within a specific time frame. The GP has 45 days to identify the replacement properties and 180 days to close. It is the role of the GP to identify suitable replacement properties that align with its’ investment strategy. The exchange defers all real property taxes (personal property is not included in the exchange), including capital gains and depreciation recapture. LPs continue to receive tax-deferred distributions from the new property’s cash flow, and their basis of the original property carries over, deferring taxes until a taxable sale occurs.

Capital Gains Taxes

A capital gain is the profit when a capital asset is sold for more than was originally paid for it, or “cost basis.” Common examples of capital assets include stocks and bonds, real estate, vehicles, collectibles, and business assets. An unrealized gain is an increase in the assets’ value while it is owned and is not taxable. When an asset is sold, a realized gain occurs and becomes subject to capital gains tax. A profit from selling assets held for one year or less is considered a short-term capital grain, and is taxed at a ordinary income tax rate, which can range from 10% to 37%, depending on the taxpayer’s income. When assets are held for more than one year and sold for profit, it becomes a long-term capital gain.

Private real estate investments are typically structured to generate long-term capital gains, which are taxed at lower rates of 15-20% for assets held over one year. For higher-income individuals, there’s also a potential net investment income tax (NIIT) of 3.8% that could increase their total capital gains tax. This tax applies to the total earnings from your investments in a given tax year, minus any related expenses.

Pass-through Deductions

Private real estate investments are typically structured as pass-through entities for tax purposes, either as limited partnerships (LPs) or limited liability companies (LLCs). In a pass-through entity, profits, losses, deductions, and credits “pass through” pro-rata to LPs, who report them on their personal tax returns via Schedule K-1 (Form 1065). Key pass-through deductions for real estate investors include depreciation, interest expense, operating expense, accelerated and bonus depreciation, and losses.

Return of Capital (ROC)

Return of capital (ROC) refers to distributions that are not taxable as income because they represent a return of the LP’s invested capital or are offset by depreciation deductions. These distributions reduce the LP’s tax basis in the partnership, deferring taxes until a sale or until distributions exceed basis.

In some scenarios, refinancing a property can lead to significant return of capital distribution for LPs. For example, the value of a property held may increase over time due to market factors, improvements made, or successful management. The GP may decide to obtain a new, larger loan based on the property’s higher appraised value. Since the new loan amount exceeds the balance of the original loan plus any loan costs, this difference results in cash proceeds distributable to the investment partners. Since this cash is not generated from the property’s operating income, the GP can distribute pro-rata shares of these proceeds to LPs as a return of capital. The amount of the ROC distribution reduces the LPs cost basis in the investment, meaning a potentially larger capital gain at a future taxable sale.

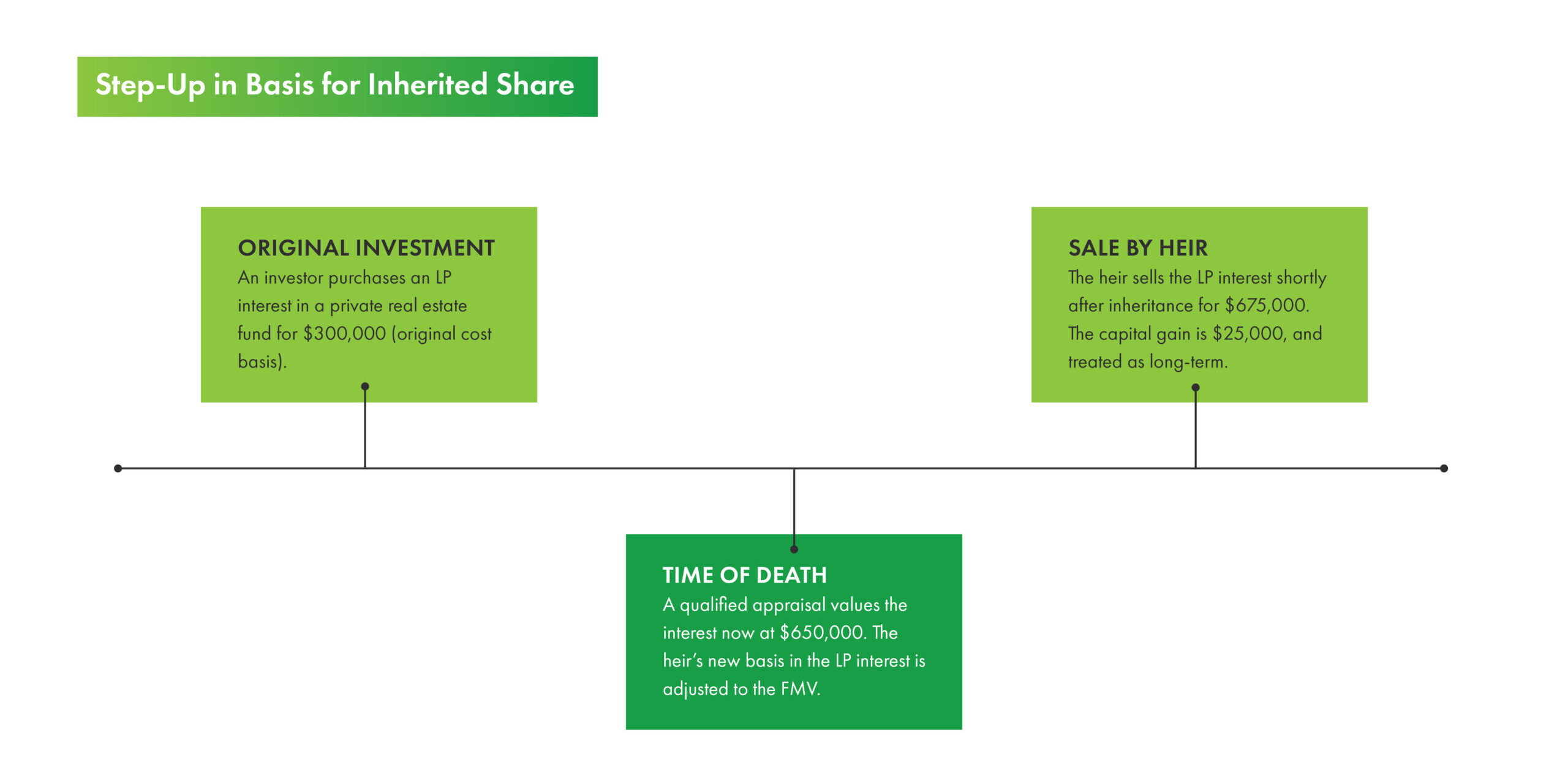

Step-up in Basis

The concept of “step-up in basis” is primarily relevant as it relates to estate planning. It is a provision in U.S. tax law that allows the cost basis of an asset inherited from a deceased person to be “stepped up” to its fair market value (FMV) as determined by a qualified appraisal at the time of the owner’s death. In short, the step-up in basis can significantly reduce or even eliminate capital gains taxes for the person who inherits the asset. When the heir sells the asset, they are only taxed on the gain that occurs after they inherit it, not the appreciation during the owner’s lifetime. If the heir sells the property, the capital gain is calculated as: Sale Price – Stepped-Up Basis. Inherited assets are always treated as long-term for capital gains purposes, even if sold shortly after inheritance.